The winter season is technically defined as: December, January and February. This is what is known as the “meteorological winter”. According to the “calendar season”, winter doesn’t officially end until the Spring Equinox, which will be this coming Monday, March 20th.

In Jackson Hole, winter isn’t over until the “ski season” ends in April. And I might add, for some Jackson Hole locals, the ski season doesn’t end until all the snow melts.

Since the meteorological winter is now behind us, and spring (March, April, May) has technically begun, I thought I would summarize this “winter’s” weather in this week’s column. In a subsequent column I will add March to the mix and give you the grand totals, for the entire “ski season”.

First, I will summarize and compare snowfall and water in the mountains. Then I will summarize snow, water, and temperatures for this winter in the Town of Jackson.

Mountain Snow

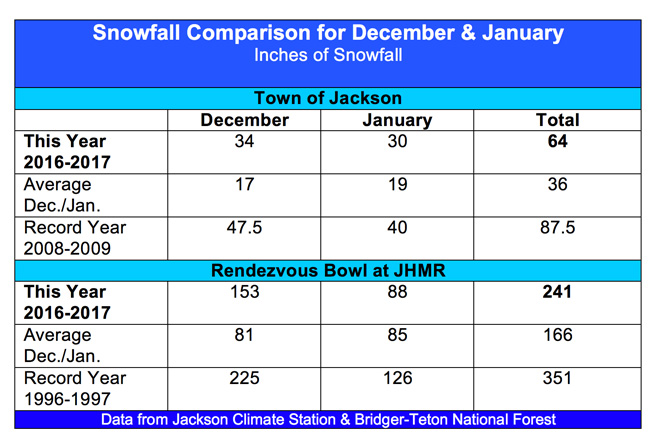

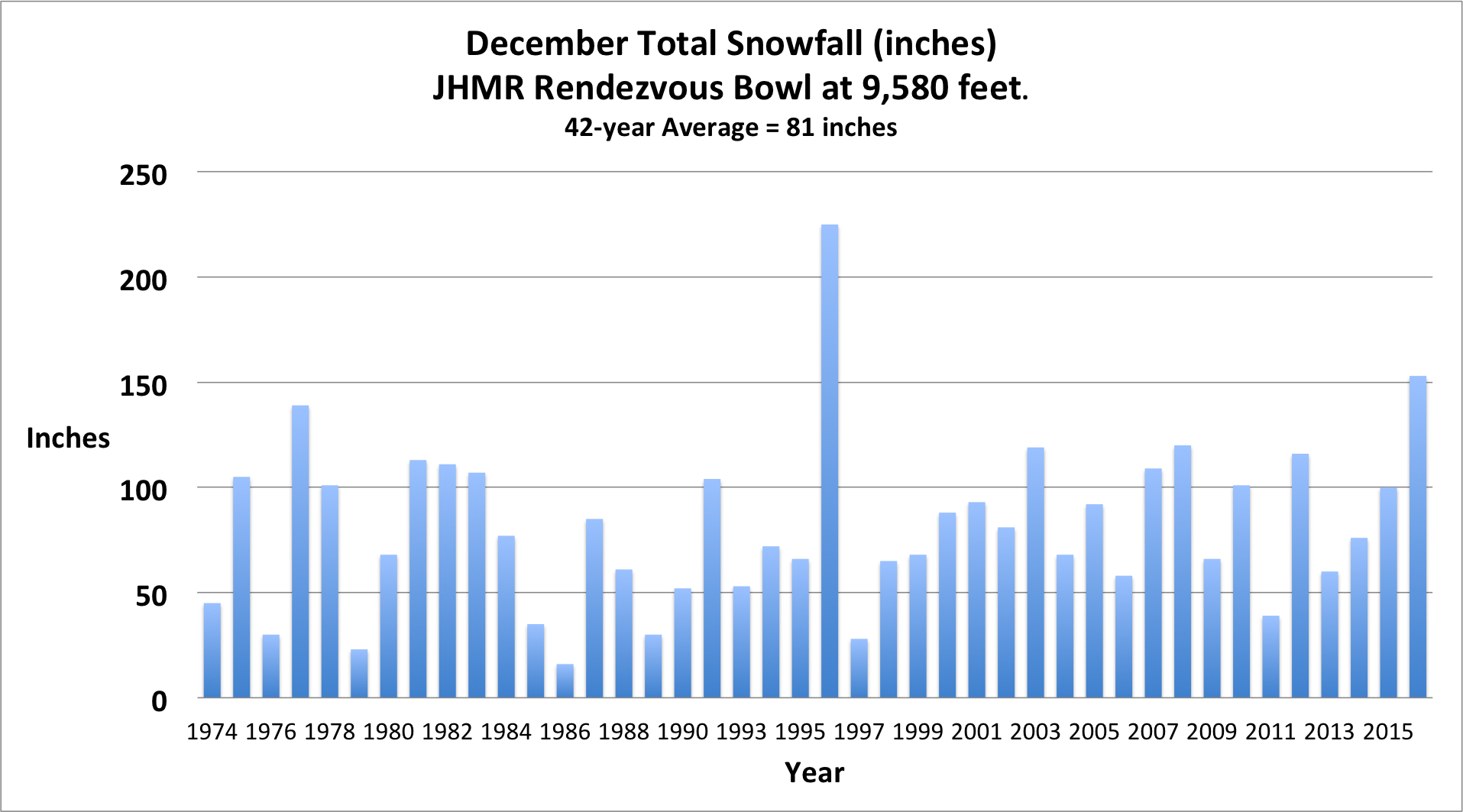

At the Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, at the 9,580-ft. elevation in Rendezvous Bowl, the total snowfall received at that location from December 1st, 2016 through February 28th, 2017 was 390 inches. That is over 32 feet of snowfall over those three months alone.

The Rendezvous Bowl weather site has the longest continuous record of snowfall on the upper mountain, and the record snowfall at that site for December through February is 417 inches, or almost 35-feet of snowfall. That was during the winter of 1996-97. The winter of 2016-17 is now the second snowiest “winter season” on the mountain, in their 40-some years of weather records. All other winters are a distant third.

At the end of the meteorological winter this year, the settled snow depth in Rendezvous Bowl was at 151 inches. Making this the deepest winter ever.

Note: In early March, Rendezvous Bowl’s snow depth reached 158 inches. That beat the old deepest snow depth record of 157 inches that occurred in late March of 1997.

Water content of the snowpack at the end of February 2017, measured at the Phillips Bench Snotel site at the 8,200 foot elevation near Teton Pass, was at 157-percent of the median. The snowpack there contained 31 inches of water, compared to an average for the end of February of 21.8 inches, or almost 10 inches more than normal.

By the way, at the end of February 1997 Phillips Bench had 37 inches of Snow Water Equivalent. Six inches more than February 2017.

Town of Jackson

Snow and water numbers in the mountains might be mind-blowing, but what happened in town this winter was nothing short of being one of the wildest weather winters on record. Snow, rain, cold, warm…..we had it all. And we had it over, and over, and over again.

Snowfall-wise: This winter stacks up with some of the snowiest. Rain events in February are the only thing that kept us from blowing away the all-time record snowfall winter. This winter, 90 inches of snowfall was measured at the Jackson Climate Station. That is 40 inches more than the long-term average for December through February. Average is 50 inches.

That ranks the Winter 2016-17 as the third snowiest winter season on record in town. February of 2008-09 holds second place with 98.5 inches, and the winter of 1968-69 still has the all-time record of 114 inches of snowfall.

Water-wise: During the three months of the winter season 2016-17 Jackson had an astonishing 11.85 inches of precipitation, almost a foot of precipitation. That completely washed away the previous record from the wettest winter ever in Jackson. The old record was 9.28 inches of water from the winter of 1964-65.

February 2017 accounted for almost half of this winter’s total precipitation, with 5.75 inches. That is five times the average for February of 1.14 inches and more than double the previous record precipitation of 2.83 inches for February, set back in 1962.

Temperature-wise: It may not seem like it recently, but Winter 2016-17 was colder than normal, overall. December was quite cold, with a mean temperature (average of high and low temperatures) that was 6-degrees colder than normal. January was even colder; with a mean temperature that was 11 degrees colder than the long-term average. February made up for some of this temperature deficit, coming in almost 7-degrees above normal.

Comparing temperatures from that other wet winter of 1964-65 to this winter, the biggest difference was that 1964-65 was warm all three month. It rained in December 1964 with high temperatures in the lower 40’s. It rained in January 1965, with highs also in the lower 40’s. It rained in February 1965, and high temperatures reached 50-degrees, on February 4th, 1965.

This winter, we never hit 40-degrees in December or January, and the winter’s highest temperature was 44-degrees on February 16th, 2017

Bottom-line: For the meteorological winter, the mountain snowpack was the deepest ever; snowfall and water amounts were second only to the winter of 1996-97. The Town of Jackson had more snow during the winters of 2008-09 and 1968-69, but broke the record for total precipitation this winter season.

Jim is the chief meteorologist at mountainweather.com and has been forecasting weather in Jackson Hole and the Teton Range for more than 25 years.

Sunday, Feb. 26th, 2017.

Sunday, Feb. 26th, 2017.