All posts by Jim Woodmencey

Horsethief Fire Weather Page

If you are really into the weather and especially weather related to fire behavior, you can follow along more closely with information posted on the NWS Riverton website page that was set up to assist the fire weather forecasters working the Little Horsethief Wildfire near Jackson,WY.

Main link is here: NWS Horsethief Fire page

I will set up a direct link to this page at the top of the Jackson Hole Forecast Page and also under the Fire Weather Information section at the bottom of the Jackson Hole Information Page on www.mountainweather.com

Some of the cool stuff of interest might be the Hi-resolution Satellite photos that show the smoke plume best when skies are clear during the day, see below:

| Hi-Resolution Visible Satellite Photo of Wyoming |

There is much more to view here, some of it is more technical fire weather forecast products & computer models, but other info of general interest is the Loop from the Web Cam on top of Teton Pass that looks towards the fire.

And also the Fire Weather Briefing Page for Teton County Emergency Managers

(click the bold print).

Posted by meteorologist Jim Woodmencey

9-12-2012

Fire Weather & Air Quality

|

Horsethief Fire September 9, 2012

|

|

First shot from Munger @ 2:00 pm

|

|

Last shot from Munger @ 3:15 pm

|

|

Taken from Rodeo Grounds in Jackson @ 5:00 pm

|

Where to Find Fire & Air Quality Info

Photos by Jim Woodmencey

Winter Weather Outlook 2012-13

(Reminder: Prices increase Sept 1st for the Jackson Hole Mountain Resort. After Sept. 16th for Grand Targhee).

Long Range Outlooks

NWS Discussions Page of mountainweather.com)

|

3-Month Outlook Maps for October-November-December 2012

|

|

|

Temperatures

|

Precipitation

|

El Nino Year

(El Nino years in blue and La Nina Years in red.)

Text submitted by meteorologist Jim Woodmencey

Cool Cumulus Clouds

Late afternoon and early evening (between about 4:30 and 8:30 pm) on Friday July 27th there were some very cool looking cumulus clouds associated with thunderstorms around the Tetons & the Jackson Hole area.

Most of these would be classified as Cumulonimbus Mammatus Clouds. That is, they were of “cumulo-form” (tall & puffy)…… They produced some rain, so they also get the suffix “nimbo”…. And, they had the mammary shapes extending from their bases, thus “mammatus”.

| Photo by Scott Guenther |

The bulbous extensions beneath the clouds are indicative of strong updrafts and downdrafts within the thunderstorm. Whether or not the thunderstorm spits out rain or hail at that point depends on if the falling precipitation within the clouds can overcome the updraft speeds.

Below is a collection of photos sent to MountainWeather after the storm, and some that I captured while on a long hike through the Tetons that day, while on a patrol with some old Jenny Lake Ranger friends of mine.

Posted by meteorologist Jim Woodmencey

|

|||||

|

|

Thunderstorms Add Needed Water

|

Total Precip January 1 through July 31

|

|

|

Year

|

Precip Inches

|

|

2000

|

9.06

|

|

2001

|

5.54

|

|

2002

|

7.63

|

|

2003

|

6.57

|

|

2004

|

8.79

|

|

2005

|

10.15

|

|

2006

|

9.44

|

|

2007

|

4.92

|

|

2008

|

9.09

|

|

2009

|

13.93

|

|

2010

|

10.74

|

|

2011

|

12.82

|

|

2012 so far = 8.21 in.

Historic Average Jan.-July = 9.34 in. Data in this table is taken from the Jackson Automated rain gauge, for comparison.

|

|

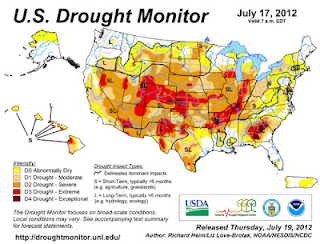

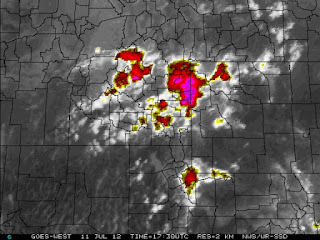

July 11, 2012 Thunderstorm Summary

|

Snow King Lightning Detector Image

(From MountainWeather ) |

Pocatello Radar Image

(Courtesy of NWS) |

|

Infra-Red Satellite Photo (NOAA)

|

Visible Satellite Photo (NOAA)

|

June 2012 Weather Review

|

June 2012 vs. June Historic Averages

|

|

|

Avg. High Temp = 75°F

|

Normal High = 72°F

|

|

Avg. Low Temp = 38°F

|

Normal Low = 37°F

|

|

Avg. Mean Temp = 56.5°F

|

Normal Mean = 54.5°F

|

|

Total Precip.= 0.20 inches

|

Normal Precip = 1.65 inches

|

|

| July 2012 Temperature Outlook |

|

| July 2012 Precipitation Outlook |

Data for June 2012 is from the USFS “automated” weather station, and is compared to the old historical record which was all taken “manually for the last 70+ years.

Fire Weather Season

The U.S. Forest Service’s Active Fire Page

Jackson Hole has been spared so far, with no thunderstorms this past week to spark any fires. We’ve been sitting under a dry & stable Southwesterly flow. But the weather not too far to the south of us over eastern Utah & western Colorado has had a few thunderstorms as a relatively narrow tongue of moisture in the upper levels of the atmosphere has extended from Arizona, northward to parts of southern Wyoming.

Some indication that the weather pattern may change by the middle or end of next week, with what looks like some monsoon moisture creeping up from the South, which would likely bring us some thunderstorms.

Posted by meteorologist Jim Woodmencey

Map images from USFS & UCAR

Wind in June

Father’s Day Wind

Down here at ground level in western Wyoming & eastern Idaho, we experienced wind gusts in the Town of Jackson of 34 mph. 40 mph at the Jackson Hole Airport, and a 53 mph gust in Grand Teton National Park, just east of Jenny Lake. At the Driggs Airport they recorded a gust of 51 mph. These winds were more of a straight-line wind, consistent in direction, from the West-Southwest, primarily.

Jet Stream map from NWS